Research

Our research focuses on quantum phenomena: Quantum Thermodynamics, Quantum Optimal Control Theory and Quantum Dynamics. In addition we have an applied research effort devoted to public safety.

Quantum thermodynamics is the study of the relations between two independent physical theories: thermodynamics and quantum mechanics. The two independent theories address the physical phenomena of light and matter. It is now possible to manipulate single atoms and ions to enable the construction of heat engines and refrigerators whose cores are comprised of asingle particle. Surprisingly, these microscopic quantum heat machines have been found to obey classical thermodynamical results, which is puzzling. It is expected that quantum eects would modify classical thermodynamics results on the atomic scale. Hence, some of the key outstanding questions in the eld of quantum thermodynamic are: What is quantum about quantum heat machines? We study the relations between the laws of thermodynamics and quantum mechanics.

Quantum Thermodynamics: A dynamical Viewpoint, Entropy 15, 2100 (2013).

Quantum heat engines and refrigerators

A quantum heat engine is a device that generates power from the heat flow between hot and cold reservoirs. The operation mechanism of the engine can be described by the laws of quantum mechanics.

The quantum heat exchanger

The quantum tricycle

Equivalence of Quantum Heat Machines, and Quantum-Thermodynamic Signatures.

Quantum thermodynamics in strong coupling: heat transport and refrigeration.

Quantum Optimal Control Theory

It is control that turns scientic knowledge into useful technology: In physics and engineering it provides a systematic way for driving a system from a given initial state into a desired target state with minimized expenditure of energy and resources. As one of the cornerstones for enabling quantum technologies, optimal quantum control keeps evolving and expanding

Training Schrödinger’s cat: quantum optimal control.

Quantum control with noisy fields

A closed quantum system is dened as completely controllable if an arbitrary unitary transformation can be executed using the available controls. In practice, control elds are a source of unavoidable noise, which has to be suppressed to retain controllability. Can one design control elds such that the eect of noise is negligible on the time-scale of the transformation? This question is intimately related to the fundamental problem of a connection between the computational complexity of the control problem and the sensitivity of the controlled system to noise.

Coherent Control of Binary reactions

We demonstrated coherent control of bond making, a milestone on the way to coherent control of photoinduced bimolecular chemical reactions. In strongeld multiphoton femtosecond photoassociation experiments, we nd the yield of detected magnesium dimer molecules to be controlled.

Ultracold Molecule Formation

We study the control and manipulation of ultracold matter making molecules out of atoms. We demonstrated that judicious shaping of a nanosecond-time-scale frequency chirp can dramatically enhance the formation rate of ultracold 87Rb2 molecules.

Open Quantum Systems: Surrogate Hamiltonian

In reality every quantum systems is open. The interaction with the environment has a profound effect. We construct and study quantum Master equations for molecular systems in condensed phases. As an alternative we are developing the method of stochastic surrogate Hamiltonian which is a wavefunction method for studying the dynamics of open quantum systems. We use the method model solar energy capture and to study quantum refrigerators.

Heat transport and a heat rectifyer.

Solar energy capture

The purpose of computational models is to gain insight. Our goal is to develope quantummodeling methods where the numeical error is under control such that the result depends only on the model. Our mehods are based on a direct solution of the time dependent schrodinger equation and he Liouville von Neumann equation.

Public Safety: Energetic materials

We study the physical chemistry of energetic materials both improvised and military grade. Our purpose is to find ways to remotly detect these materials using spectroscopic methods. The globalization of terror requires that we have to employ our scientic knowledge to develop methods to protect the public. As a result we have initiated studies of improvised explosives such as TATP and military grade such as TNT.

Open Quantum Systems: Surrogate Hamiltonian

Open Quantum systems

No quantum system can be completely isolated from its environment. As a direct result a quantum system is never pure \(Tr\{ \bf \rho^2 \} < 1\). A pure state is unitary equivalent to a zero temperrature grounds state frobidden by the third law of thermodynamics. A complete description of a quantum system requires to include the environment. The ourcome of this process is that oltimately we end with the state of whole universe describned by a wavefunction\(\Psi\).

Even if the combined system is pure and can be described by a wavefunction \(\Psi\), a subsystem in general cannot be described by a wave function. This observation motivated the formalism of density operators and matrices introduced by John von Neumann in 1927 and independently, but less systematically by Lev Landau in 1927 and Felix Bloch in 1946. In general the state of a subsystem is described by the density operator \(\rho_S\)and an observable by the scalar product\(< {\bf A}>= (\rho \cdot {\bf A })= Tr\{ \rho {\bf A} \}\). There is no way to know if the combined system is pure from the knowledge of the observales of the sybsystem. In particular if the combined system is entangled the system state is not pure.

Open system dynamics

The theory of open quantum systems seeks an economical treatment of the dynamics of observables that can be associated with the system. Typical observables are energy and coherence. Loss of energy to the environment is termed quantum dissipation. Loss of coherence is termed quantum decoherence. The reduction problem is difficult resulting in a diversity of approaches that have been attempted. A common objective is to derive a redced descrption where the system's dynamics is considered explicitly and the bath is described implicitly.

When the interaction between the system and the environment is weak a time dependent perturbation theory seems appropriate. The typical assumption is that the system and bath are initially uncorrolated \(\rho(0) =\rho_S \otimes \rho_B\).The idea has been originated by F. Bloch and followed by Redfield known as Redfield equation. The drawbak of the Redfield eqution is that it does not conserve the positivity of the density operator.

An alternative derivation employing projection operator techniques is know as Nakajima–Zwanzig equation. The derivation highlight the problem that the reduced dynamics is non-local in time: \(\partial_t{\rho }_\mathrm{S}=\mathcal{P}L{{\rho}_\mathrm{rel}}+\int_{0}^{t}{dt'\mathcal{K}({t}'){{\rho }_\mathrm{S}}(t-{t}')}.\)The effect of the bath is hidden in the momrey kernel \(\kappa(\tau)\). Additional assumptions of a fast bath are required to lead to a time local equation \(\partial_t \rho_S = {\cal L} \rho_s\).

Another approach emeres as a analogue of classical dissipation theory develped by R. Kubo and Y. Tanimura . This approach is connected to Hierarchical equations of motion which embeds the density operator in a larger space of auxillary operaors such that a time local equation is obtained for the whole set.

A formal construction of the Markovian local equation of motion is an alternative to a reduced derivation. The theory is based on an axiomatic appproach. The basic starting point is a completely positive map. The assumption is that the inital sysem-environmnt state is uncorrelated \(\rho(0) =\rho_S \otimes \rho_B\)and the combined dynamics is unitary. Such a map falls under the category of Kraus map. The most general type of Markovian and time-homogeneous master equation describing non-unitary evolution of the density matrix ρ that is trace-preserving and completely positive for any initial condition is the Gorini–Kossakowski–Sudarshan–Lindblad equation or GKSL equation. For observales it becomes:\( \frac{d}{dt}A=+{\frac {i}{\hbar }}[H,A]+{\frac {1}{\hbar }}\sum _{k=1}^{\infty }{\big (}L_{k}^{\dagger }AL_{k}-{\frac {1}{2}}\left(AL_{k}^{\dagger }L_{k}+L_{k}^{\dagger }L_{k}A\right){\big )} \). The family of maps generated by the GKSL equation forms a quantum dynamical semi-group. In some fields such as quantum optics the term Lindblad superoperator is often used to express the quantum master equation for a dissipative system. EB Davis, derived the GKSL Markovian master equations using perturbation theory thus fixing the flaws of the Redfield equation. Davises construction leads the stationary solution to thermal equilibrium.

In 1981, Amir Caldeira and Anthony J. Leggett proposed a simplifying assumption in which the bath is decomposed to normal modes representd as harmonic oscillators linearly coupled to the system. As a result the influence of the bath can be summerized by the bath spectral function. This method is known as the Caldeira–Leggett or harmonic bath model. To proceed typically, the path integral description of quantum mechanics is employed.

The harmonic normal-mode bath leads to a physically consistent picture of quantum dissipation. Nevertheless its ergodic properties are too weak. The dynamcs does not generate wide scale entangelment between the bath modes.

An alternativ bath model is a spin bath. At low temperature and weak system-bath coupling therse two bath models are equivalent. But for higher excitation the spin bath has strong ergodic properties. Once the system is coupled significant entagelment is generated between all modes. A spin bath can simulate a harmonic bath but the oposite is not true.

Basic Construction of the surrogate Hamiltonian

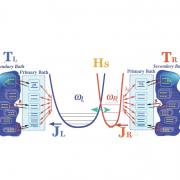

In the stochastic surrogate Hamiltonian approach, the system device is subject to dissipative forces due to coupling to primary baths. In turn, the primary baths are subject to interactions with a secondary bath:

HT=HS+HB+HB''+HSB+HBB''

where HS represents the system, HB represent the primary baths, HB'' the secondary baths, and HSB the system–bath interaction. HBB'' the primary/secondary baths’ interactions. The system Hamiltonian HS describes molecular nuclear modes: The molecular Hamiltonian has the form:

\({\bf H_S} = \frac{{\bf P}^2}{2m} +V({\bf R})\)

The reduction in computational complexity is obtained by splitting the representation to a system that requires a full quantum description and a bath described implicitly. The final outcome is equations of motion for relevant dynamics, which are computationally tractable.

The bath is described by a fully quantum formulation. The method employed is the stochastic surrogate Hamiltonian \cite{k238,k250}. Briefly, the bath is divided into a primary part interactingwith the system directly and a secondary bath which eliminates recurrence. The primary bath Hamiltonian is composed of a collection of two-level-systems.

\({\bf H_B} ~~=~~ \hbar \sum_j \omega_j {\bf \sigma^+_j} {\bf \sigma_j } \)

The energies \(\omega_j\) represent the spectrum of the bath and \({\bf \sigma_{\pm}}\) are bath excitation/de-excitation operators. The system-bath interaction \(\bf H_{SB}\) can be chosen to represent different physical processes. Specifically we choose an interaction leading to vibrational relaxation:

\({\bf{H}_{SB} }= \hbar f({\bf R_s}) \otimes \sum_{j}^{N} \lambda_{j} ({\bf{\sigma}_{j}^{\dagger}}+\bf{\sigma}_{j})\) ,

where \(f({\bf R_S})\)) is a dimensionless function of the system nuclear coordinates \({\bf R_S}\) and \(\lambda_j\)is the system-bath coupling frequency of bath mode j. when the system-bath coupling is characterized by a spectral density \(J(\omega)=\sum_{j} |\lambda^2|\delta (\omega-\omega_j) \)then \(\lambda_j =\sqrt{J(\omega_j)/\rho_j} ~~and ~~\rho_j=(\omega_{j+1}-\omega_j)^{-1} \) is the density of bath modes.The secondary bath is also composed of noninteracting two-level-systems (TLS) at temperature T with the same frequency spectrum as the primary bath. At random times the states of primary and secondary bath modes of the same frequency are swapped at a rate

\(\Gamma_j \) .

The swapping procedure permits description of both dephasing and energy relaxation. The final results are obtained by averaging over the stochastic realizations. The swap makes the bath effectively infinite. Each swap operation eliminates the quantum correlation between the bath mode swapped and system and other bath modes.

This loss of system-bath correlation leads to dephasing.

The stochastic surrogate Hamiltonian approach is a fully quantum treatment of system-bath dynamics. The method is not Markov constrained, and is based on a wavefunction construction. The system and bath are initially correlated, since the initial state is the combined thermal state generated from the coupled system-bath Hamiltonian by propagating in imaginary time

until the correlated ground state is obtained. The transport properties of the surrogate Hamiltonian are consistent with the second law of thermodynamics. Additional entanglement is generated by the dynamics. Convergence of the model is obtained by increasing the number of bath modes and the number of stochastic realizations.

A central operation in the stochastic surrogate Hamiltonian is the swap: replacing one spin component of the bath with another. An important technical issue is how to perform this operation within a global wavefunction description of the system and primary bath.

Decoherence is a fundamental process where a quantum system loses its wave properties enabling interference. As a result classical behavior emerges. Decoherence is a clear concept studied at least for 50 years nevertheless, it is still ill defined, it cannot be associated with a unique observable. New quantum technologies require control on the decoherence and knowledge on the transition from quantum to classical behavior. In the implementation of possible future quantum technologies and quantum information processing fast decoherence is destructive. A signature of decoherence is purity loss where purity is defined by  .

.

- Gil Katz, David Gelman, Mark A. Ratner, and Ronnie Kosloff Stochastic surrogate Hamiltonian, J. Chem.Phys. 129 034108 (2008).

- Erik Torrontegui, and Ronnie Kosloff Activated and non-activated dephasing in a spin bath New Journal of Physics, 18, 093001 (2016).

Current team

Public Safety: Energetic materials

Decomposition of Condensed Phase Energetic Materials: Interplay Between Uni and Bimolecular Mechanisms

Activation energy for the decomposition of explosives is a crucial parameter of performance. The dramatic suppression of activation energy in condensed phase decomposition of nitroaromatic explosives has been an unresolved issue for over a decade. We rationalize the reduction in activation energy as a result of a mechanistic change from unimolecular decomposition in the gas phase to a series of radical bimolecular reactions in the condensed phase. This is in contrast to other classes of explosives, such as nitramines and nitrate esters, whose decomposition proceeds via unimolecular reactions both in the gas and in the condensed phase. The thermal decomposition of a model nitroaromatic explosive, 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT), is presented as a prime example. Electronic structure and reactive molecular dynamics (ReaxFFlg) calculations allowed us to directly probe the condensed phase chemistry under extreme conditions of temperature and pressure, identifying the key bimolecular radical reactions responsible for the low activation route. This study elucidates the origin of the difference between the activation energies in the gas phase ( 62 kcal/mol) and the condensed phase ( 35 kcal/mol) of TNT. On the basis of these findings, the different reactivities of nitro-based organic explosives are rationalized as an interplay between uni- and bimolecular processes. The reaction kinetics of the thermal decomposition of hot, dense liquid TNT was studied from first-principles-based ReaxFF multiscale reactive dynamics simulation strategy. The decomposition process was followed starting from the initial liquid phase, decomposition to radicals, continuing through formation of carbon-clusters products, and finally to formation of the stable gaseous products. We find that the decomposition of liquid and solid TNT are similar both leading to the formation of soot.

current team

Quantum Coherent Conrol

Quantum Coherent Control

It is control that turns scientific knowledge into technology. The general goal of quantum control is to manipulate dynamical processes at the atomic or molecular scale, typically using external electromagnetic field. The objective of quantum optimal control is to devise and implement shapes of pulses of external field or sequences of such pulses, that accomplish a given task in a quantum system in the best possible manner.

The challenge of manipulating nature at the quantum level has a huge potential for current and future applications. Quantum optimal control is a part of the effort to engineer quantum technologies from the bottom up. Currently the emerging quantum technologies are based on superposition, entanglement and many-body quantum states. Quantum control is thus a strategic cross-sectional field of research, enabling and leveraging current and future quantum technology applications.

The field of quantum control has been initiated by the idea of controlling chemical reactions [1–5]. It was soon realised that the principles of quantum control through interfering pathways is universal and spread to other fields such as quantum information [6,7]. A recent overview has been published which emphasises the future prospects of the field [8]. Coherent control can be applied directly to controlling matter waves using a BEC as a source of matter waves. We have pioneered this idea.

Despite the success and proliferation of coherent control the dream of controlling chemical reactions has not been achieved. To fill this gap our recent efforts concentrated on control of binary reactions. As a first step in coherent control of binary-chemical reactions we studied both experimentally and theoretically the photoassociation of hot Mg2[9]. We were able to identify two mechanisms of coherent control. The first is based on multiphoton interference pathways. The second is vibrationally assisted [10]. The pulse shaping was carried out by a spatial light modulator in the frequency domain. The other extreme case is coherent control of photoassociation of ultracold Rb2[11]. The duration of the control pulse is four orders of magnitude longer than the pulse used for Mg2 photoassociation. For the Rb2 case the pulse shaping was carried out in the time domain. In both the photoassociation of the Mg2 and the Rb2 the reaction leads to a significant reduction of translational entropy. The next step in control of binary reactions should be devoted to processes of the type AB + C → A + BC → AC + B. This will require a combined experimental and theoretical effort.

Photoassociation of hot Mg2

A natural meeting point between Quantum thermodynamics and coherent control is to develop method to cool internal degrees of freedom of molecules [12]. We originated this quest of cooling internal degrees of freedom of molecules by broad band excitations [13–14]. This scheme has been realised experimentally in broad band cooling the vibrations of Cs2 [15–18] and rotational cooling of trapped molecular ions [19]. The current challenge is a simultaneous cooling of both vibrational and rotational degrees of freedom [20]. The difficulty emerges from the large separation of time scales.

The coherent control required to achieve these tasks is of an open quantum system. It would seem that decoherence in open systems will destroy the interference required to generated control. Nevertheless in some cases the the environment allows control which otherwise could not be achieved [21, 22]. An outstanding issue is coherent control in weak field. For isolated systems for target operators that commute with the system hamiltonian phase only coherent control is impossible [23]. We were able to extend this theorem of no phase control to Markovian evolution of open systems [24]. Nevertheless there is unpublished experimental data indicating asymmetry between positive and negative chirp in weak field absorption. If verified, it would indicate to an experimental procedure to unravel non-Markovian dynamics.

The issue of controllability has not been resolved. What can be controlled by interference? What is the minimal time to achieve such a control? What is the optimal control protocol? These issues deserve further study in the context of open quantum systems. An important issue is the influence of noise. In particular the unavoidable noise on the controller. Such noise is fast relative to the timescale of the controlled system. Can one circumvent the influence of this noise by cooling the system? In the context of quantum information this is known as adding an ancilla qubit.

Coherent Control has become an essential component in achieving quantum gates [6]. What is unique is the requirement of extremely high fidelity. A related issue is how to obtain a quantum gate under noisy conditions [7]. The same type of gates for example swap gates can be used for quantum heat engines.

All practical engines require active control to achieve their goals. Quantum heat engines are no exception, they require monitoring and feedback. But in quantum mechanics constant monitoring can change the state of the working medium, for example measuring energy will destroy coherence. We only started to tackle this issue [27] which is related to quantum measurement and control [25].

Active quantum control requires measurement and feedback [27]. This issue has not been studied in a thermodynamical context. Quantum thermodynamics and quantum control are natural mates. Quantum control is the enabler of the coherent manipulations required in a truly quantum heat device. Advance in one field has immediate consequence in the other.

References

Quantum Dynamics Tool Kit

The propagator is a realization of the evolution operator a mapping step which carries the wavefunction from time t to t': \(\Psi(t)={\bf U}(t) \Psi(0)\)

The stage of events is the time-energy phase space. The time dependent Schrodinger equation:

\(i \hbar \frac{\partial}{\partial t} \Psi = {\bf H} \Psi\)

A formal solution is obtained by:

\(\Psi(t) = e^{-\frac{i}{\hbar} {\bf H} t} \Psi(0)\)

where \({\bf U}(t) = e^{-\frac{i}{\hbar}{\bf H}t}\)

with the equation of motion

\(i \hbar \frac{\partial}{\partial t}{\bf U} = {\bf H} {\bf U}\)

Our numerical approach is to expand the evolution operator in a polynomial in H. [1,2].

For time independent hamiltonian operators we found that the best polynomial expansion is based on the Chybychev expansion.

A more difficult problem is when we have explicit rime dependence in the Hamiltonian either directly or through nonlinearity: \({\bf H } \equiv {\bf H}(\psi,t)\).

This results in a nonlinear equation of motion. In addition, we include an inhomogeneous source term \(s(t)\). The time-dependent nonlinear inhomogeneous Schr¨odinger equation reads:

\(i \hbar \frac{\partial}{\partial t} \Psi = {\bf H}(t,\Psi) \Psi+s(t)\)

Quantum Thermodynamics

Quantum Thermodynamics

Quantum thermodynamics is the study of the interplay between two independent physical theories: Thermodynamics and quantum mechanics. Both theories address the same physical phenomena of light and matter. Learning from example has been the motto of thermodynamics since its inception by Carnot [1]. Comparing the predictions of the two theories on a specific example has been a source of insight. Einstein in 1905, while studying radiation in a cavity, postulated that the requirement of consistency between thermodynamics and electromagnetism require light to be quantised [2].

Thermodynamics is notorious in reducing the physical description to only a few variables. Systems at equilibrium can be fully characterised by one variable: their energy. The opposite is true in quantum mechanics where complexity of a complete description scales exponentially with the number of degrees of freedom or the number of particles. All operating quantum devices that convert heat to work or pump heat out of a cold bath operate far from equilibrium. This is reflected by the fundamental tradeoff between efficiency and power. A dynamical description of such devices require additional variables. Quantum theory can in principle supply a dynamical framework able to predict the evolution of systems far from equilibrium. Nevertheless the complexity of the treatment makes direct predictions impossible[3].

The field of quantum thermodynamics aims to bridge the two viewpoints [4, 5]. Our approach to the problem was always based on learning from an example; constructing a quantum model of a heat device and comparing the two theories [6–8]. A fundamental theoretical tool of quantum thermodynamics is the system-bath partition. The idea is toseek a reduced description of the system - meaning an explicit equation of motion for the system alone, where the bath is described implicitly. This is the turf of the theory of open quantum systems [9]. A major construction is the Lindblad Gorini-Kosakowsku-Sudarshan (LGKS) equation of motion known as the quantum Master equation [10, 11]. The equation describes Markovian dynamics (no memory) generated from a completely positive map [12].

Under this dynamical description at all times the system and bath are uncorrelated i.e. have a tensor product structure [4]. As a result system variables are well defined and can be directly related to thermodynamical predictions.

Recently we have shown by analysing an example of heat transport through a quantum wire that solutions based on local L-GKS violates the second law of thermodynamics [13]. We identified conditions where heat was flowing from the cold to the hot bath. This analysis is a typical learning from an example: Comparing the predictions of quantum theory and thermodynamics. The remedy to the discrepancy could be traced to the local construction. Employing a global construction of the master equation known as Davis construction, restored the consistency [14]. This method is based on the weak coupling limit between the system and bath. It requires a pre-diagonalization of the global system. For example the whole chain composing the quantum wire. The outcome of the procedure is a more complex L-GKS quantum master equation.

An important outcome of the analysis is that the popular approach to assemble Lego-like models of quantum devices is bound to violate the second law of thermodynamics. Quantum devices are global and therefore require an integrated approach.

Quantum heat engines and quantum refrigerators are the next level of complexity. A quantum model of such a device is composed of a system, a hot and cold baths and an external driving mechanism. If a wire has two leads, a quantum heat engine has three external leads referred to as a quantum tricycle [15]. Naive constructions of L-GKS equations for time dependent driving represented by a time dependent Hamiltonian violate the second law [16]. A thermodynamical consistent treatment has been worked out only for the case of periodic driving. An L-GKS master equation is derived by Floquet analysis separating the driving to its Fourier components [17, 18]. The result is a separate Master equation for each frequency component. Such a theory has been employed for models of heat engine and refrigerators [16, 19–21]. These models have been employed to explore the tradeoff between power and efficiency in thermal devices showing remarkable consistency with the phenomenological theory of finite time thermodynamics [22–26]. Due to the complexity of the Floquet procedure only very simple model system are amenable to analysis.

Can we construct a quantum dynamical theory consistent with thermodynamics which goes beyond the weak coupling Markovian limit? Can this model deal with a general time dependent external driving that could be the outcome of quantum control?

Recently [27] we have developed a quantum non-Markovian scheme for general system bath dynamics which is consistent with thermodynamics. The method is termed Stochastic Surrogate Hamiltonian (SSH). The main idea is to partition the bath to a primary and secondary part. The dynamics of the primary bath and the system is generated by a combined Hamiltonian. A wavefunction description is employed for the combined system. For this purpose we have employed a spin bath. The typical size of the combined Hilbert space is 108 − 109 states.

Quantum large and complex systems have a remarkable property termed quantum typicality. The expectation of almost any local property converges to a value which is independent of the details of the initial state [28–32]. We have observed that the system observables in SSH method converge extremely rapidly to typical values when the number of bath modes increases. As a result an extremely small number of stochastic realisations of wave-function calculations are sufficient to evaluate the systems properties.

The role of the secondary bath is to establish an outgoing thermodynamical boundary condition. We achieve this goal by stochastically applying partial or full swap between a pair of spins of the primary and secondary baths. The bath temperature is imposed by choosing the population of the secondary bath to conform to Boltzmann statistics. In addition the phase of these spins is random.

Since the spins that are swapped are in resonance the energy transfer between the primary and secondary bath is pure heat [33]. We have put the scheme to test in a heat transport model based on a molecular system coupled at each side to a hot and cold bath. The SSH, independent of the system construction, always showed the correct energy flow from the hot to the cold bath. In addition we discovered a heat rectifying effect; asymmetry in the heat current when the connection to the leads was reversed [34, 35].

We have thus established a fully quantum system-bath scheme which is not based on perturbation theory. At all times the system and bath are entangled which eliminates a basic assumption in the weak coupling theory. The system dynamics is non-Markovian and can be strongly driven.

Convergence can be verified by increasing the number of bath modes. The SSH reliance on wavefunctions has significant computational advantages. The scaling of the basic operation φ = Hˆ ψ is semi-linear with the size of Hilbert space (∝ N log N ). Time propagation is carried out by a

Chebychev polynomial expansion of the evolution equation which computation effort scales linearly with the propagation time [36, 37]. Recently we developed a new Chebychev propagator specifically for time dependent Hamiltonains [38] overcoming the time ordering issue. The stochastic surrogate Hamiltonian is the best candidate to generate quantum simulations of mesoscopic systems. Since the method is wavefunction based we anticipate Hilbert space sizes of 235 ∼ 1011.

The power of the stochastic surrogate Hamiltonian was next put on test on a model of a molecular refrigerator. A periodic electric field was used to drive the system through the molecular dipole. With sufficient driving the natural heat current was reversed pumping heat from the cold to hot bath. Sufficient driving power was required to overcome the natural heat leak flow from the hot to cold bath [39]. Effects of strong coupling were observed: the cooling power saturated and then was suppressed when the driving amplitude increased. This led to a performance graph of efficiency vs power mimicking known result from macroscopic refrigerators [40]. This means that a single quantum device composed for example from a molecule has performance characteristics of a macroscopic air conditioner.

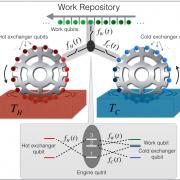

FIG. 1: The quantum tricycle, a three lead quantum device coupled simultaneously to a hot, cold, and power reservoir. A reversal of the heat currents constructs a quantum refrigerator. The tricycle topology is the template of the autonomous quantum heat device. At steady state the first and second laws of thermodynamics are indicated.

The combined detailed analysis carried out by many groups of quantum heat devices [8, 41–46] has led to a the surprising conclusion: The devices closely mimic their macroscopic counterparts. The efficiency is restricted by the Carnot efficiency. The hallmark of the tradeoff between efficiency and power, the Novikov-Curzon-Ahlborn efficiency at maximum power, is obtained in the high temperature limit of both continuous and reciprocating quantum models [47, 48]. Exceptions are either the result of erroneous analysis neglecting the global structure of quantum mechanics or the use of baths that can deliver both heat and work. Such baths, are nicknamed quantum fuels [49–52], include coherence which can be directly transferred to work.

This analysis has raised the alarming question: what is quantum in quantum thermo- dynamics? Does each engine type require a separate analysis or can we identify universal behaviour? Recently we addressed this challenge [53]. The key was an analysis of reciprocating heat engines; the four stroke Otto engine. The next step was to establish the limit of zero cycle time obtained by allocating less time for each of the strokes. Obviously we obtain less work per cycle, nevertheless in the limit of zero cycle time finite power is obtained. Formally this is the limit of small action on each stroke, where action can be measured in units of planks constant. We found that the limit of small action engines is universal. Four-stroke two-stroke and continuous cycles have the same power and efficiency. A necessary condition for power production could be traced to quantum coherence maintained throughout the cycle. Using this result we could define a quantum signature of operation using only thermodynamical performance characteristics

The role of coherence in quantum reciprocating engines can be explored by partitioned the propagator into distinct strokes. For example the quantum Otto cycle is composed of four strokes: Two adiabats where the scale of energy of the working system is modified externally, and two isochores where heat is transferred from the hot or cold bath. Each of these strokes can be described by a CP map; a propagator. The total cycle propagator is the product of the stroke propagators. A necessary condition for extracting power or for refrigeration is that the stroke propagators do not commute.

Two extreme possibilities can be identified. The field which is termed the stochastic limit, the cycle is characterised by population of the energy levels. The only quantum feature in this limit is the discrete spectrum of the Hamiltonian. In this case the non- commutativity is the result of permutation and thermalisation propagators. Coherence allows another source of non-commutative phenomena. The coherence represents operators which do not commute with the Hamiltonian. When the Hamiltonian does not commute with itself at different times fast dynamics generates coherence on the adiabats. As a result the adiabatic propagator will not commute with the thermalisation propagator. In the limit of small action only the coherence can generate a sustainable finite power or finite cooling rate [53, 54].

A related question is the role of entanglement in quantum heat engines. It was suggested that entanglement can enhance the performance [55] in a model of a three qubit refrigerator. This analysis has been criticised using a more refined model [20] claiming that in the point of maximum cooling power no entanglement exists. At this point I would state that the role of entanglement in heat devices is inconclusive.

An integral part of a heat engine is an energy storage device, either temporary such as a flywheel or more permanent such as a rechargeable battery. Quantum treatments address this issue by adding an explicit term to the Hamiltonian of the system. This term should be able to store large amounts of energy therefore a typical choice for a model is an unbounded Hamiltonian. The common choice is an harmonic oscillator [56, 57]. The immediate consequence is that the storage device carries entropy as well as energy. Now if the fluctuations grow out of control the storage device becomes useless [58]. In addition when large amplitude of stored energy is accumulated it causes back reaction on the system bath coupling. As a result the energy storage operation is stopped. We analysed a model of a two qubit engine coupled to a harmonic oscillator representing a flywheel.

The function of the flywheel is to store work and to release it on demand increasing the instantaneous power beyond the power of the engine. At certain operating conditions we could reduce the dynamics of the flywheel to an oscillator driven by an inverse temperature L-GKS equation. Under these conditions the fluctuations diverge. To correct for this problem we added a quantum controller composed of weak measurement and feedback [58]. When the rate of energy current from the heat engine matches the weak measurement strength then the extraction efficiency is maximised.

The most studied model of a quantum heat bath is composed of a set of uncoupled harmonic oscillators linearly coupled to the system. The framework is of normal modes and the linear coupling cannot generate entanglement between the modes. The model has been employed extensively in the study of thermalisation [9]. The linear harmonic model is consistent with the second [59, 60] and third law of thermodynamics [61]. Nevertheless the linear model has been criticised for too weak ergodic properties [62]. One obvious aspect is that the model does not contain a mechanism of internal thermalisation of the different bath modes. What is missing conceptually is a heat exchanger. A device that filters out a thermal distribution in a small frequency range for example a two level system [63]. By incorporating such a device we were able demonstrate quantum equivalence in the strong coupling regime.

Collective effects of quantum heat engines have only recently been addressed [64]. Is there an advantage of operating such engines in series or in parallel? An attractive idea is to combine such engines in series and to transfer coherence from one engine to another. As a result one can obtain an effect of feeding the engine with quantum fuels enhancing the overall efficiency [65].

The III-law of thermodynamics is where one can expect quantum features. Two independent formulations of the III-law of thermodynamics exist, both originally stated by Nernst [66–68]. The first is a purely static (equilibrium) one, also known as the ”Nernst heat theorem” : phrased:

• The entropy of any pure substance in thermodynamic equilibrium approaches zero as the temperature approaches zero.

The second formulation is dynamical, known as the unattainability principle:

• It is impossible by any procedure, no matter how idealised, to reduce any assembly to absolute zero temperature in a finite number of operations [68].

There is an ongoing debate on the relations between the two formulations and their relation to the II-law regarding which and if at all, one of these formulations implies the other [69–72]. Quantum considerations can illuminate these issues. Insight has been obtain by the analysis of specific cases. The quantum refrigerator models differ in their operational mode being either continuous or reciprocating. When optimised for maximum cooling rate the energy gap of the receiving mode should scale linearly with temperature ωc ∼ Tc [15, 19, 73–75]. Once optimised the cooling power of all refrigerators studied have the same universal dependence on the coupling to the cold bath. This means that the III-law depends on the scaling properties of the heat conductivity γc(Tc) and the heat capacity cV (Tc) as Tc → 0.

Theoretical challenges to the III-law have been proposed [76] based on anomalous spectral function. We find this spectral function to violate the stability criterion of the combine system-bath leading to imaginary frequencies [77]. A recent paper claims that higher order terms in the system bath coupling will lead to residual heating of the baths thus stopping the cooling process at finite temperature [61]. The quantum nature of the III-law needs further analysis connecting different approaches.

Experimental realisations of single component quantum heat devices

The template for an experimental realisation is a single quantum component coupled through leads to heat baths performing a thermodynamical task of converting heat to work or pumping heat against a thermal gradient. The minimal requirement is quantum systems with three leads or coupling wires to a hot cold and work reservoir [78]. The field of quantum information has motivated the development of highly controllable quantum experimental platforms. They include ion traps [79], Josephson junction based devises [80], quantum dots [81], NV centres in diamonds [82] and NMR spectrometers [83]. All these devices can be reengineered to operate as thermal machines

with the advantage that the requirement for high fidelity operations can be relaxed. These realisations can be either continuous or reciprocating based on quantum gates. The first example of this new era of experiments is a realisation of a quantum Otto cycle implemented by a single ion in a trap [84]. Other realisations based on other platforms will be realised soon. For example, a suggestion of a Josephson based device was published [85].

Laser cooling is a crucial technology for implementing quantum devices. When the temperature is decreased, degrees of freedom freeze out and systems reveal their quantum character. Inspired by the mechanism of solid state lasers and their analogy with Carnot engines [86] it was realised that inverting the operation of the laser at the proper conditions will lead to refrigeration [87, 88]. A few years later a different approach for laser cooling was initiated based on the doppler shift [89, 90].

In this scheme, translational degrees of freedom of atoms or ions were cooled by laser light detuned to the red of the atomic transition. Unfortunately the link to thermodynamics was forgotten.

Currently laser cooling is among the basic enablers of quantum technology. It can operate to the level of a single atom or single ion in a trap [91–94]. These are templates of quantum heat devices, where entropy is carried away by scattering light. Other non- local quantum entropy generation methods should be explored. The methods of laser cooling should be unified in a thermodynamical framework.

FIG. 2: A heat machine scheme with heat exchangers (gears). Various engine types can be implemented in this scheme by controlling the coupling function to the engine (ellipse). In each cycle, the gears turn and the work repository shifts so that new particles enter the interaction zone (gray shaded area). The heat exchangers enable the use of Markovian baths while having non-Markovian engine dynamics. This includes strong coupling and/or short time evolution. In this model, the work is stored in many batteries (work qubit in green); (b) the engine level diagram. This machine is based on two-body energy conserving unitaries. This is in contrast to other machines that employ three-body interaction.

References